I often take notes and jot down observations when I read academic/industry papers. Thinking of a name for this series ‘Gossips in Distributed Systems’ seemed apt to me, inspired by the gossip protocol with which peers in these systems communicate with each other which mimics the spread of ideas and technologies among practitioners and people alike. The goal of this series would be to do a round-up of any new concepts or papers in computer science (often in distributed systems but not always) and share my thoughts and observations.

Today, we are going to talk about the Physalia paper from AWS: “Millions of Tiny Databases”. This is inspired by Physalia or Portuguese man-of-war (pictured), a siphonophore, or a colony of organisms. Overall, the paper, even though slightly on the longer side, is chock full of details and best practices pertaining to design, architecture, and testing of distributed systems.

Given the size of the paper and the wide gamut of topics that it touches, we will be discussing only a few aspects of the paper in this post along with some observations. In subsequent sequels, we will go into others in further detail.

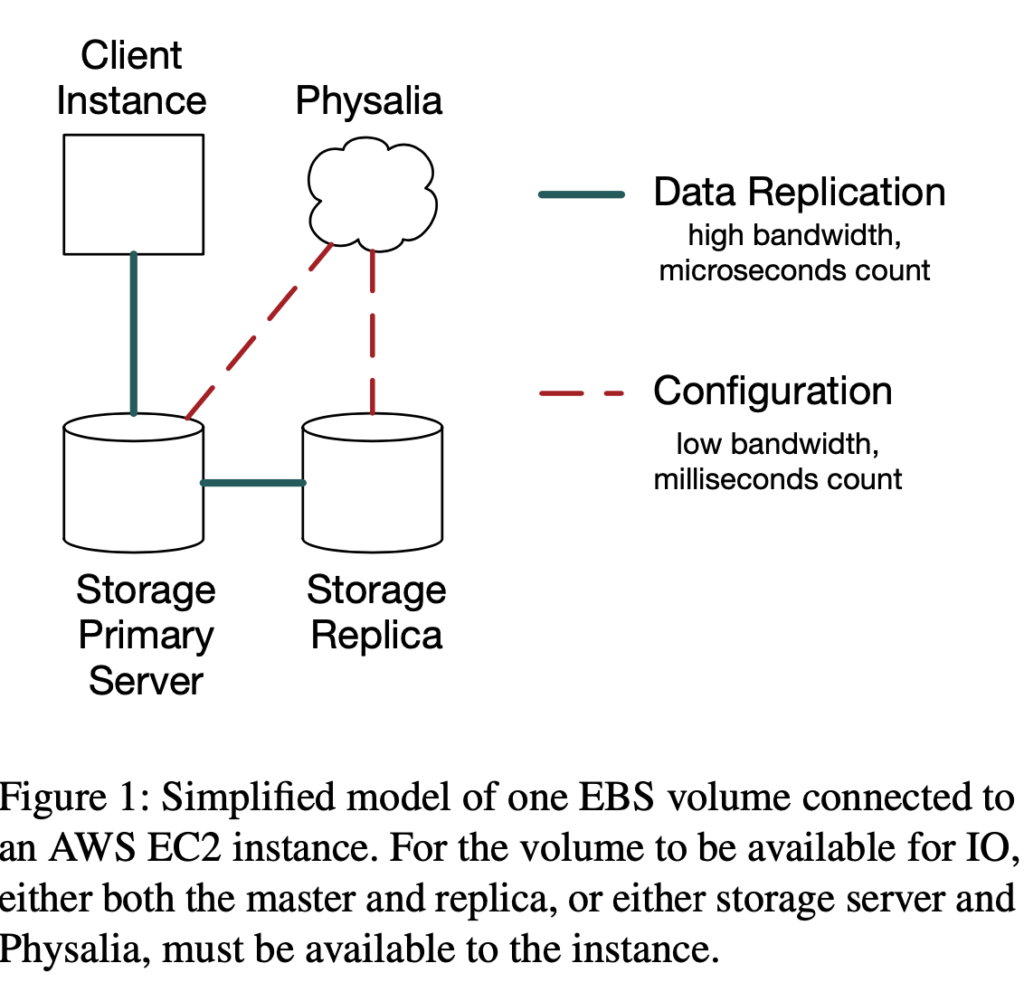

Before proceeding ahead, the present EBS architecture with Physalia has a primary EBS volume (connected to EC2 instance) and a secondary replica, and data flowing from instance to primary and replica in that order. Also, this chain replication is strictly within an Availability Zone (AZ) mainly due to inter-AZ latencies being prohibitive. The pre-Physalia architecture had a similar replication chain but with the control plane also being part of EBS itself rather than a separate database (which we will soon find out was not a good idea).

Raison d’être

All good-to-great systems have a story that necessitated their existence. In this case, it was an outage of the us-east-1 region in 2011 caused by overload and subsequent cascading failure which necessitated a more robust control plane for failure handling. The postmortem of that outage is here, it is quite long and wordy, so I will summarize it here.

Continue reading “Gossips in Distributed Systems: Physalia”